Why Indigenous Knowledge and Biocultural Conservation Matter — and What Science Says About It

In 2026, the world stands at a crossroads. Crises around climate change, biodiversity loss, cultural erosion, and social inequality converge in ways that defy traditional solutions. Within this complexity, Indigenous Peoples maintain practices that, through generations, show how humans and the natural world are not separate, they are part of the same living process.

For too long, Western science and policymaking have treated ecosystems as machines to manage and “nature” as something apart from human life. But in the growing field of biocultural conservation, scientists and communities alike are reclaiming a much older truth: biological diversity and cultural diversity are inseparable, and Indigenous knowledge systems deeply reflect this.

Here we explore three recent scientific publications that together trace emerging theory and practice of biocultural conservation and Indigenous knowledge systems:

A systematic review of biocultural conservation practice showing how biological and cultural diversity are being linked in environmental science (Lukawiecki et al., 2022).

A critical analysis of whether Indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) has a future in a world dominated by Western science and economic development (Gómez-Baggethun, 2021).

A comprehensive review of Spanish-language literature on how ILK is conceptualized and used in biocultural approaches to sustainability, exploring meanings, applications, threats, and transformative potentials of ILK (Burke et al., 2023).

Taken together, these studies offer a robust scientific foundation for the spiritually informed, community-led conservation work supported by organizations like the IMC Fund.

1. What Is Biocultural Conservation — and Why Is It Gaining Steam?

To many readers, terms like biocultural conservation or biocultural approaches might sound like academic jargon. But the underlying idea is profound and simple:

Humans are not separate from nature. Our cultures, practices, languages, and worldviews are embedded in ecosystems that we help sustain, and ecosystems shape our cultures in return.

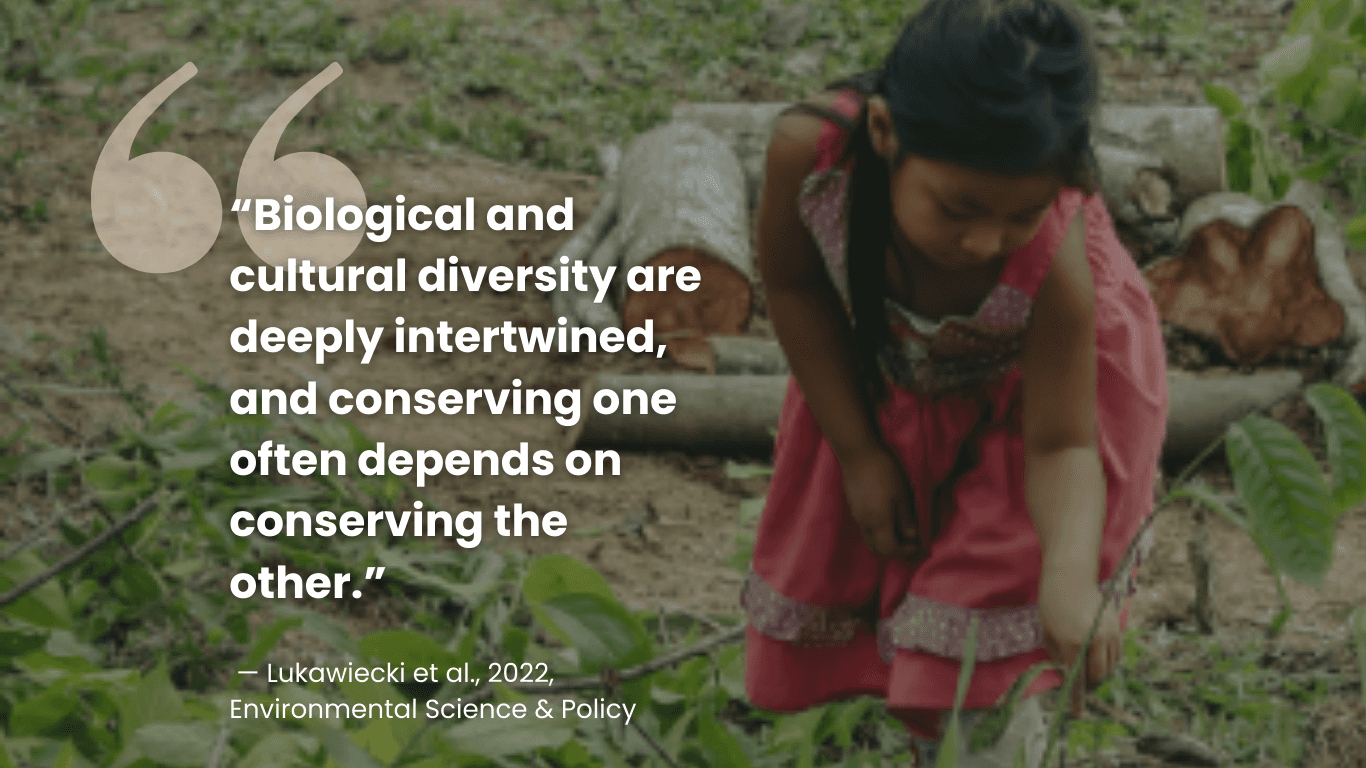

This is the core argument of Lukawiecki et al. (2022) in their systematic review of how biocultural perspectives are being operationalized in conservation science. Operationalizing means moving from theory into actual conservation practice, with real programs and community action.

Biocultural Means More Than Nature + Culture

Historically, Western conservation treated biodiversity (species, ecosystems) as separate from human culture. But biocultural approaches start with the understanding that biological diversity and cultural diversity (languages, practices, spiritual traditions, relational worldviews) are mutually reinforcing and co-evolved over thousands of years. In other words, losing cultural diversity often means losing biodiversity, and vice versa. This is not a presumption but an empirical observation, supported by global patterns showing regions rich in biological diversity tend also to be culturally diverse.

Lukawiecki and colleagues reviewed published literature and found that while biocultural concepts are widely discussed, actual applied examples in conservation practice are still emerging. Yet where they do occur, these models often embody principles long practiced by Indigenous Peoples: shared stewardship, relational ethics toward all beings, and community authority in decision-making.

(Lukawiecki et al., 2022)

This is direct scientific validation of what Indigenous and local communities have always known: conservation cannot be abstract or technocratic. It must engage with ways of life, meanings, stories, and practices. Biocultural conservation involves protecting whole systems — ecological, cultural, spiritual, and linguistic — not just isolated species or spaces.

Culture must be a foundation for conservation.

2. Can Indigenous and Local Knowledge Survive — and Lead?

If biocultural conservation recognizes Indigenous knowledge as central, an obvious question emerges: Does Indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) have a future in global science and policy, or is it at risk of being co-opted or erased?

This is the question Erik Gómez-Baggethun tackles in his influential 2021 article. He asks not just whether ILK can be included, but whether it can survive on its own terms.

Western Science and ILK: A Troubled History

For much of the 20th century, Indigenous knowledge was treated as quaint, anecdotal, or merely practical: “technical knowledge” with limited theoretical value. ILK was often used instrumentally: scientists borrowed local insights to improve crop yields or natural resource management, but rarely acknowledged Indigenous worldviews or authority.

Gómez-Baggethun shows how this began to change only in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, as scientific institutions started recognizing that ILK provides indispensable insights into long-term ecological patterns, landscape processes invisible to short-term scientific measurements, and resilience strategies that help communities adapt to environmental change.

Indeed, major institutions like the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) now affirm that Indigenous knowledge systems are empirically sound and contribute to sustainability research at global scales.

Instrumentalization vs. Autonomy

One danger identified by Gómez-Baggethun is that ILK may be instrumentalized — incorporated only insofar as it serves Western scientific goals — without respecting Indigenous systems as autonomous ways of knowing.

This creates subtle forms of exclusion and power asymmetry, where ILK is cited in science and policy but Indigenous Peoples remain marginalized in decision-making.

So, Does ILK Have a Future?

Gómez-Baggethun argues that it does, if the structures of science and policy change to make ILK and Indigenous communities equal partners.

This means:

Accepting ILK as a valid epistemology, not a supplement to science.

Supporting Indigenous authority over knowledge production.

Reforming institutional processes that currently privilege Western frameworks.

The IMC Fund encourages this shift: not simply documenting Indigenous knowledge or using it selectively, but centering Indigenous leadership and worldviews in environmental governance.

(Gómez-Baggethun, 2021)

3. What the Spanish-Language Literature Says About ILK and Biocultural Sustainability

The third publication, Burke, Díaz-Reviriego, Lam & Hanspach (2023), offers something especially valuable: a systematic review of Spanish-language scientific literature on biocultural approaches to sustainability.

Much research in environmental science is published in English, limiting access and recognition of work done in other languages. This review brings to light dozens of studies from Latin America and Spain that explore ILK in the context of biocultural sustainability.

How ILK Is Conceptualized

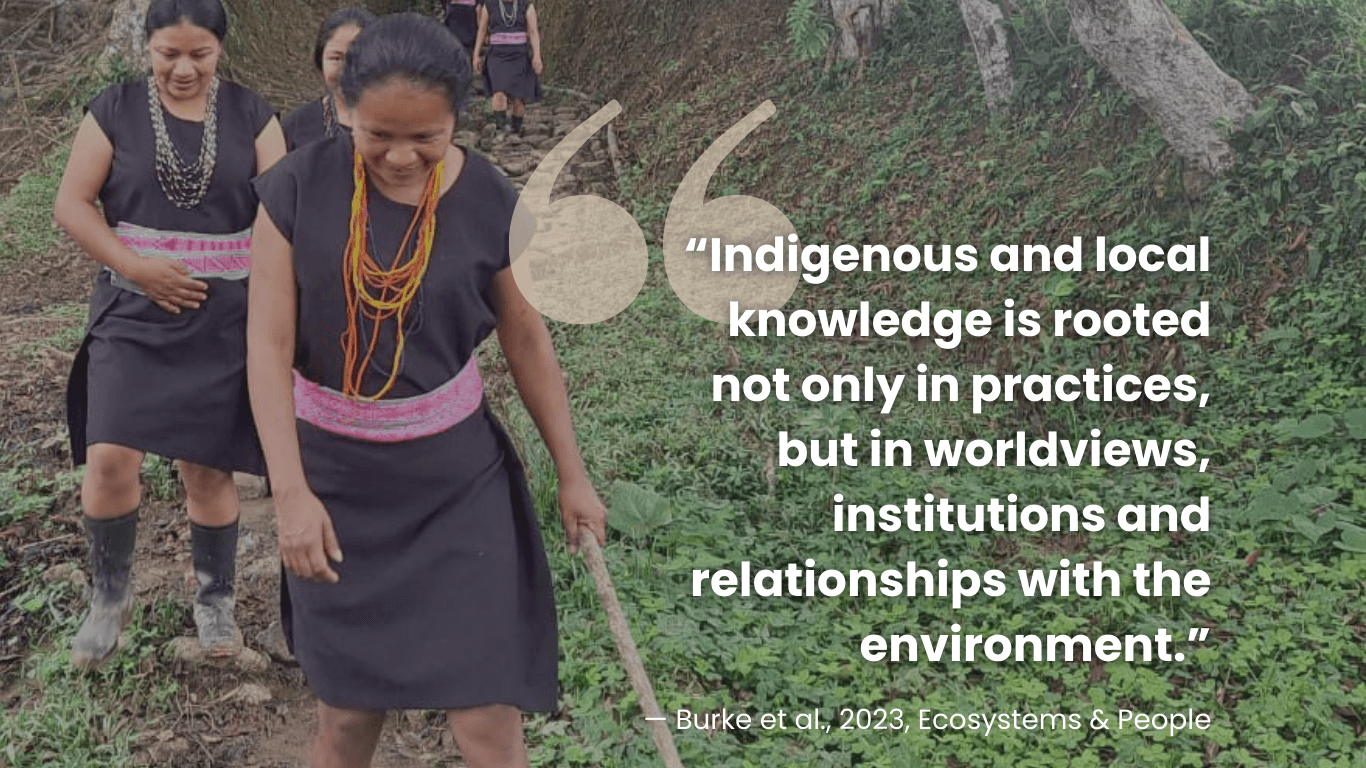

The study analyzed 72 Spanish-language scientific papers that explicitly focus on biocultural approaches. It found that ILK is described using a variety of terms and dimensions, but several core aspects recur:

Practices — techniques and systems for managing ecosystems, agriculture, medicinal plants, etc.

Local and empirical knowledge — deep familiarity with species, landscapes, and processes.

Worldviews — spiritual meanings, cosmologies, rituals, taboos, and norms that shape human–nature relationships.

Social institutions — community governance, norms of reciprocity and solidarity embedded in cultural systems.

(Burke et al., 2023)

Importantly, most researchers emphasized that ILK is tightly linked to specific biocultural contexts: it is place-based, shaped by continuous interaction with a local environment over generations.

This counters simplistic views of Indigenous knowledge as static or universal. ILK is lived, adaptive, and richly diversified across regions, communities, and histories.

Applications of ILK: Conservation and Transformation

Most of the reviewed studies (92%) describe how ILK contributes to biocultural sustainability in two main ways:

a. Biodiversity Conservation in Practice

Many papers highlight that ILK underpins everyday practices that conserve biodiversity, such as:

In-situ conservation of agrobiodiversity (traditional seeds and crops).

Oral narratives and practices that maintain ecological memory.

Legal and social resistance to destructive extractive industries.

For example, in southern Chile, the Yagan community’s narrative about the hummingbird not only conveys cultural meaning but encodes ecological knowledge about water, species interactions, and ecosystem health. In other regions, Indigenous communities have successfully resisted mining or logging to protect landscapes essential for cultural and biological diversity.

This mirrors multiple global studies showing that lands stewarded by Indigenous Peoples often contain the most intact ecosystems on Earth.

b. Pathways to Sustainable Futures — But Disagreement on What “Sustainability” Means

The literature documents a plurality of views on whether ILK aligns with mainstream notions of sustainable development.

Some researchers argue ILK provides practical pathways to resilient local economies and environmental stewardship, complementary to, or even enhancing, sustainable development frameworks.

Others go further: they reject the very idea of “development” rooted in Western economic growth models. These scholars propose that Indigenous worldviews like Buen Vivir (a concept from Andean cosmologies meaning “good living in harmony with all relations”) represent entirely different paradigms that challenge mainstream sustainability.

This is an important nuance: ILK may offer alternative visions of human flourishing that go beyond GDP or consumption metrics.

(Burke et al., 2023)

Bridging Knowledge Systems: Opportunities and Struggles

A central theme in the Spanish-language literature is the tension between complementarity and co-production of knowledge:

Complementarity assumes that ILK and scientific knowledge can be harmonized — one fills gaps in the other.

Co-production goes deeper — it treats both knowledge systems as distinct but able to generate new shared understandings through collaboration and mutual respect.

Many scholars note that bridging systems is a power issue more than it is a technical challenge. Scientists often dominate collaboration, and power asymmetries limit Indigenous participation. Real co-production requires recognizing Indigenous self-determination and authority, not merely including Indigenous people in predefined research roles.

The authors conclude that biocultural approaches can help shape alternative futures — but they must address power, context, and Indigenous self-determination to avoid repeating colonial dynamics.

(Burke et al., 2023)

4. What This Means for the IMC Fund and Biocultural Conservation

Taken together, these three publications offer powerful validation of the principles underlying the IMC Fund’s support for Indigenous-led, spiritually informed biocultural conservation and show how it is grounded in scientific research.

Scientific literature increasingly recognizes that biological and cultural diversity are co-constitutive and that protecting one without the other is incomplete.

Indigenous and local knowledge is empirical, dynamic, and adaptive, embodying sophisticated ecological understanding built through generations of practice, observation, and adaptation.

Conservation actions must support Indigenous authority and self-determination.

Token inclusion of Indigenous knowledge is insufficient. ILK must be recognized as a valid source of insight in its own right, and Indigenous Peoples must shape research priorities, governance, and policy.

Threats to biocultural systems are intertwined. Environmental degradation, cultural erosion, linguistic loss, and political marginalization reinforce one another. Solutions must be holistic — addressing ecology, culture, governance, and economics together.

5. Final Thoughts: A Science That Honors Spirit

The science of biocultural conservation points toward a future where:

Nature and culture are not opposing forces.

Conservation is not about excluding people from landscapes but protecting life with its peoples.

Indigenous wisdom offers pathways that speak to both empirical resilience and relational ethics.

Spiritual understandings of interdependence are not separate from science — they enrich it.

In the face of unprecedented global crises, conservation that ignores culture is like trying to heal a body while ignoring the nervous system that connects every part.

Indigenous knowledge systems anchored in place, relationships, and long-term ecological memory are not relics of the past. They are alive, intact and must be respected on their own terms.

Supporting Indigenous-led, spiritually informed biocultural conservation is scientifically supported and urgently needed.

Selected Full Citations

Burke, L., Díaz-Reviriego, I., Lam, D. P. M., & Hanspach, J. (2023). Indigenous and local knowledge in biocultural approaches to sustainability: a review of the literature in Spanish. Ecosystems and People, 19(1), 2157490. https://doi.org/10.1080/26395916.2022.2157490

Gómez-Baggethun, E. (2021). Is there a future for indigenous and local knowledge? Journal of Peasant Studies, 49(6), 1139–1157. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2021.1926994

Lukawiecki, J., Wall, J., Young, R., & Gonet, J. (2022). Operationalizing the biocultural perspective in conservation practice: A systematic review of the literature.Environmental Science & Policy, 136, 369–376.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2022.06.016